Sinking on the way to Tinian

by John Whitbeck

(Submitted February, 2019)

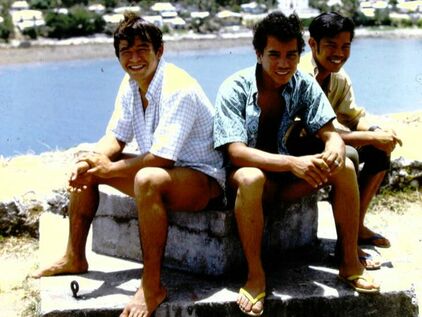

John Whitbeck (1969) on the left

John Whitbeck (1969) on the left

August 10, 1969, at around 6:30 pm, an 11 foot boat with a 3 horse power engine, sank in the ocean west of the channel between south Saipan and north Tinian. Leo Pangelinan, John Whitbeck, and Dieter Doerr had left Sugar Dock Chalan Kanoa, earlier that Sunday in the boat.

The original plan for the boat trip was to go to Managaha for the day and then come back to Sugar Dock. John had informed his neighbors and fellow Peace Corps Volunteers, Neil and Nina, of his plans for the day, stating they should be back that evening. As the boat neared Managaha, the ocean was unusually calm that day. Dieter, who had recently jumped ship from a tramp steamer visiting Saipan, wanted to see what Tinian was like. Leo explained to Dieter that to get to Tinian, we needed to travel many miles more than the five miles across the channel.

At this point, Dieter, who had borrowed the boat, wanted to go back to Sugar Dock to get a number of full gas cans so we could keep fueling the three horse engine to travel the more than 20 miles of open ocean to reach Tinian. After clearing the reef off Sugar Dock the three headed south west to get to Tinian, planning on traveling off the west coast of Tinian to reach the dock on the south shore of Tinian. The ocean was peaceful with little wind and smooth waves.

Just as the sun started going down, the boat was entering the currents that shift back and forth in the channel between the islands. The waves started getting bigger and cresting a bit. I was sitting at the front of the boat facing the outboard motor when I noticed water starting to come into the back of the boat. We had nothing to bail with as the boat continued to fill up. We also had no life preservers. Because of the weight of the motor, the back of the boat sank first and the boat started to sink further and further. Dieter, who was steering the boat, immediately jumped in the ocean and started swimming away. Leo stayed with me, explaining the best way to get to land.

The original plan for the boat trip was to go to Managaha for the day and then come back to Sugar Dock. John had informed his neighbors and fellow Peace Corps Volunteers, Neil and Nina, of his plans for the day, stating they should be back that evening. As the boat neared Managaha, the ocean was unusually calm that day. Dieter, who had recently jumped ship from a tramp steamer visiting Saipan, wanted to see what Tinian was like. Leo explained to Dieter that to get to Tinian, we needed to travel many miles more than the five miles across the channel.

At this point, Dieter, who had borrowed the boat, wanted to go back to Sugar Dock to get a number of full gas cans so we could keep fueling the three horse engine to travel the more than 20 miles of open ocean to reach Tinian. After clearing the reef off Sugar Dock the three headed south west to get to Tinian, planning on traveling off the west coast of Tinian to reach the dock on the south shore of Tinian. The ocean was peaceful with little wind and smooth waves.

Just as the sun started going down, the boat was entering the currents that shift back and forth in the channel between the islands. The waves started getting bigger and cresting a bit. I was sitting at the front of the boat facing the outboard motor when I noticed water starting to come into the back of the boat. We had nothing to bail with as the boat continued to fill up. We also had no life preservers. Because of the weight of the motor, the back of the boat sank first and the boat started to sink further and further. Dieter, who was steering the boat, immediately jumped in the ocean and started swimming away. Leo stayed with me, explaining the best way to get to land.

Leo pictured on the left

Leo pictured on the left

Leo and I shed all of our clothing except for our underpants. We did the side stroke to eliminate as mush splashing as possible. This was because, even after dark, the sharks use the channel as a feeding area. It was now completely dark and there was no moon. Leo told me that we needed to keep a red light on top of a tower on Saipan in view to the left of our direction.

We swam for hours, with no sound or view to see if we were making progress or if we were drifting further away from land in the channel currents. Finally, just as the sun started coming up, the silence we had experienced all night was broken by the sound of the surf hitting the barrier reef and cliff on the north side of Tinian. After swimming for hours in darkness and silence, this was my first realization that we had made some progress. During those hours of swimming, my legs would cramp and I had to stop, reach down and pull on my toes so that I could keep swimming. Each time I had to control my sense my body drifting deeper and deeper.

This also caused me to swallow a certain amount of salt water, which meant that my tongue was so swollen that I could not talk, and had to breath through my nose. With the sound of the surf, I had a surge of adrenaline. I needed that badly because the surf was building up as it approached a narrow fringing reef before crashing against the cliff behind the reef.

To reach the cliff we had to climb, we needed to body surf at the crest of a wave big enough not to let us be smashed into the reef. When the right wave appeared, Leo shouted "go!" we were able to ride the crest and then lock arms so that we had four legs to help prevent us from being dragged back into the ocean. As our feet were being dragged over living coral, some of the coral became embedded in the bottoms of my feet. Fortunately, the cliff was not too high and we were finally on land.

At that time, the northern end of Tinian was mostly jungle, full of insects and leaves that cut your skin. But at least we were on land. As we made our way south, we could see small planes that seemed to fly back and forth over the shore of the island. Finally, after hours of trekking through the jungle, we were able to find the taxiways of the old airport that the Japanese had built during World War II. Once we were able to reach the entrance to the airport, we could follow the dirt road that led south to the village. There was pasture and cattle on both sides of the road. After a while, we reached a cattle tank full of water. The top layer had about 5 inches of algae, but I dunked my head in and drank water. By now the bottoms of my feet really hurt and were still bleeding. I sat down by the water tank and rested while Leo continued to head down the road.

We swam for hours, with no sound or view to see if we were making progress or if we were drifting further away from land in the channel currents. Finally, just as the sun started coming up, the silence we had experienced all night was broken by the sound of the surf hitting the barrier reef and cliff on the north side of Tinian. After swimming for hours in darkness and silence, this was my first realization that we had made some progress. During those hours of swimming, my legs would cramp and I had to stop, reach down and pull on my toes so that I could keep swimming. Each time I had to control my sense my body drifting deeper and deeper.

This also caused me to swallow a certain amount of salt water, which meant that my tongue was so swollen that I could not talk, and had to breath through my nose. With the sound of the surf, I had a surge of adrenaline. I needed that badly because the surf was building up as it approached a narrow fringing reef before crashing against the cliff behind the reef.

To reach the cliff we had to climb, we needed to body surf at the crest of a wave big enough not to let us be smashed into the reef. When the right wave appeared, Leo shouted "go!" we were able to ride the crest and then lock arms so that we had four legs to help prevent us from being dragged back into the ocean. As our feet were being dragged over living coral, some of the coral became embedded in the bottoms of my feet. Fortunately, the cliff was not too high and we were finally on land.

At that time, the northern end of Tinian was mostly jungle, full of insects and leaves that cut your skin. But at least we were on land. As we made our way south, we could see small planes that seemed to fly back and forth over the shore of the island. Finally, after hours of trekking through the jungle, we were able to find the taxiways of the old airport that the Japanese had built during World War II. Once we were able to reach the entrance to the airport, we could follow the dirt road that led south to the village. There was pasture and cattle on both sides of the road. After a while, we reached a cattle tank full of water. The top layer had about 5 inches of algae, but I dunked my head in and drank water. By now the bottoms of my feet really hurt and were still bleeding. I sat down by the water tank and rested while Leo continued to head down the road.

Leo's brother John

Leo's brother John

As he continued walking, I could see a small Datsun truck coming toward us. Someone was coming from the village to check on their cows. The truck stopped to pick up Leo and then came on to pick up me. The guy in the truck then took us back to the village. The guy driving the truck gave me the shirt and pants to wear that you see in the picture. There were several nurses with an office in the village. They had me lie on a table while they used scalpels and tweezers to get the live coral out of my feet. Then my feet were bandaged and from that point, I had to be lifted and carried.

Neil and Nina had notified Jessie that I had not returned the previous evening. Managaha was checked to see if I was still there. I learned that the small planes flying overhead were because Jessie had asked the coast guard on Guam to try and find me. Of course, Leo's Mom was notified of what happened. That morning while Leo and I were hiking through the jungle, a search boat had spotted the small boat that sank about 10 feet under. Once Leo's mom was informed that the boat had been found, friends and relatives started gathering in her home, preparing for a wake. Once this was reported back to Saipan, the Peace Corps started to prepare for the publicity for a dead volunteer.

Later Monday afternoon, a fairly large and fast boat came to take us back to Saipan. It was nearly dark when we were approaching Sugar Dock. There was a large crowd of people on Sugar dock. I felt embarrassed because I had to be carried off the boat. Leo had me carried to his mom's house. When we entered, the house was full of people gathered for the wake.

In the traditional Chamorro culture, when a person dies, that person personally visits relatives, especially mothers, to tell them that they have died. The people in Leo's home were waiting for Leo to tell his mom that he was dead. Even though he was sixteen at the time, Leo is the bravest person I have known.

Neil and Nina had notified Jessie that I had not returned the previous evening. Managaha was checked to see if I was still there. I learned that the small planes flying overhead were because Jessie had asked the coast guard on Guam to try and find me. Of course, Leo's Mom was notified of what happened. That morning while Leo and I were hiking through the jungle, a search boat had spotted the small boat that sank about 10 feet under. Once Leo's mom was informed that the boat had been found, friends and relatives started gathering in her home, preparing for a wake. Once this was reported back to Saipan, the Peace Corps started to prepare for the publicity for a dead volunteer.

Later Monday afternoon, a fairly large and fast boat came to take us back to Saipan. It was nearly dark when we were approaching Sugar Dock. There was a large crowd of people on Sugar dock. I felt embarrassed because I had to be carried off the boat. Leo had me carried to his mom's house. When we entered, the house was full of people gathered for the wake.

In the traditional Chamorro culture, when a person dies, that person personally visits relatives, especially mothers, to tell them that they have died. The people in Leo's home were waiting for Leo to tell his mom that he was dead. Even though he was sixteen at the time, Leo is the bravest person I have known.