Kit Porter Van Meter Marianas Collection & NMI PCV Memories

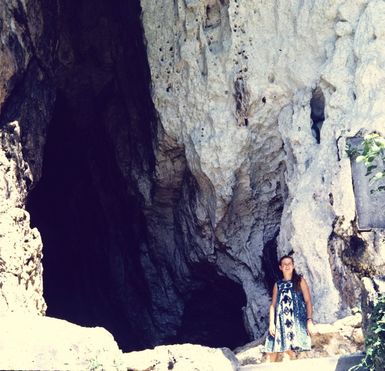

Standing by the entrance of the cave we took shelter in during Typhoon Gilda (1967)

Standing by the entrance of the cave we took shelter in during Typhoon Gilda (1967)

Something was crawling over my legs while I was half in this world, between sleep and wake, and I had no idea what it was. I eventually remembered that I was in a cave; the roaring noise was the typhoon outside, still raging after three days; the damp spot where I laid my head was from water running down the stalactites far above that had been growing through the centuries. Thankfully, the crawling on my legs was just a baby whom I guided back toward her mother resting nearby. The cave was illuminated by coke bottles filled with oil, topped by lit rags, which dotted the cave. The bottles were surrounded by people playing card games, gossiping or singing softly accompanied by a guitar.

Most of the villagers were in this cave. The rest had found shelter in one of the smaller caves scattered within the cliff wall which formed the boundary for one end of the village—SongSong Village—the only one on the island of Rota in the Mariana Chain. A few people had stayed in the cement Catholic Church for the first day of the storm, but during the incredible blue sky and sunshine of the hour when the eye of the storm went over the village, they too hurried into the cave. Those just joining us spoke of their fears that the roof would blow off even though it was the church. The men went out at that time to get food and barely made it back, needing to be pulled up against the wind on the last few steps. These stairs to the cave were built by the Japanese when they used the cave as a hospital during World War II. Some had worried about the dead souls that might bother us during the night. The fears quickly subsided though since they were Japanese spirits who would have no living family to call on in the cave. We were safe from the souls, who could, if they called you, be more dangerous than the storm. (KPV Oct. 9th, 1985)

Most of the villagers were in this cave. The rest had found shelter in one of the smaller caves scattered within the cliff wall which formed the boundary for one end of the village—SongSong Village—the only one on the island of Rota in the Mariana Chain. A few people had stayed in the cement Catholic Church for the first day of the storm, but during the incredible blue sky and sunshine of the hour when the eye of the storm went over the village, they too hurried into the cave. Those just joining us spoke of their fears that the roof would blow off even though it was the church. The men went out at that time to get food and barely made it back, needing to be pulled up against the wind on the last few steps. These stairs to the cave were built by the Japanese when they used the cave as a hospital during World War II. Some had worried about the dead souls that might bother us during the night. The fears quickly subsided though since they were Japanese spirits who would have no living family to call on in the cave. We were safe from the souls, who could, if they called you, be more dangerous than the storm. (KPV Oct. 9th, 1985)

|

The storm was Typhoon Gilda. It had been on a direct path toward Guam, a possession of the United States since 1898, at one end of the Marianas Chain. However, around 3:00AM Monday November 13, 1967, when three hours away from Guam, the storm slowed and veered Northwest making a path directly for the Northern tip of Rota, a part of the Northern Mariana Islands included in the U.S. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) since 1947. Its sustained winds were 110 to 120 miles per hour with gusts of 150 MPH (but probably higher as equipment on the island failed at that speed) -- the strongest typhoon to hit Rota since 1946. The press called it a killer typhoon.

My then husband, Greg, and I had only been in the village for a couple of months and had not understood exactly what was happening when the Girl Scouts came to help board up the house and pack everything into suitcases; I probably would not have packed without their help. It is hard to know what’s going to happen exactly when you have never been through a typhoon before. Our house was two rooms up on poles, with an outside area for the cooking fire and the washing slab. We did not even have a hammer, but that did not make any difference as people arrived with everything needed. The whole village, which was about four blocks long and three blocks wide nestled on a neck of land between a bay and the ocean, was filled with the noise of hammering as windows and doors were sealed off. Even though there was plenty of space around the island, all of the buildings were built close together. No one dared live outside the village because the spirits could bother you if you slept away from people. During Peace Corps training a few months earlier we had been taught about the different types of storms we’d see: tropical depression, tropical storm, and typhoon. The Mariana Islands were called “typhoon alley.” Storms formed around Truk in the Eastern Caroline Islands, hit the Marianas and then went on to slam Japan and/or the Philippines. We were told there would be so many typhoon warnings that we would get tired of them. The list of what we should pack included: a day’s worth of food, first aid kit, and radio. |

Typhoon conditions on impending storms were set by the Commander Naval Forces Marianas who used the information from U.S. Navy and Air Force meteorologists at the Fleet Weather Central/Joint Typhoon Warning Center on Guam. The USAF 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron at Anderson Air Force Base, Guam, would fly into the eye of the storm to gather and then relay information. (The Spinning Winds by Dorothy Fritzen, 1972)

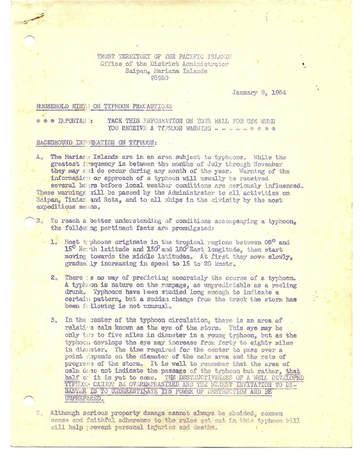

Now, 50 years later, I am reviewing a faded mimeograph:

Now, 50 years later, I am reviewing a faded mimeograph:

|

HOUSEHOLD HINTS ON TYPHOON PRECAUTIONS:

***IMPORTANT: TACK THIS INFORMATION ON YOUR WALL FOR USE WHEN YOU RECEIVE A TYPHOON WARNING*** TTPI, Office of the District Administrator, Saipan, Jan 8, 1964. “A typhoon is nature on a rampage, as unpredictable as a reeling drunk.” Typhoon Condition IV: Typhoon gales possibly within 72 hours. Due to the proximity of Saipan to the area of generation of typhoons and the possibility during all seasons of the year of typhoons, CONDITION IV is in effect at all times. Typhoon Condition III: Typhoon gales or winds of 50 knots (60 MPH approx.) or more anticipated within 48 hours. Typhoon Condition II: Typhoon gales or winds of 50 knots or more anticipated within 24 hours. Typhoon Condition I: Typhoon gales or winds of 50 knots or more anticipated within 12 hours. Five shelters are listed for Saipan, but the District Administrator in consultation with the mayor will designate Rota’s and Tinian’s. |

Preparations are listed for each condition. At Condition II children are let out of school. At Condition 1 we should “be prepared to receive word to evacuate at any moment.” And since we had never been in a typhoon before, we took the instructions very seriously. We packed the three days’ worth of food recommended on the radio. When we were in Typhoon Condition 1 people started coming by our home saying that it was time to go. An informal walking procession began through the village and up the Japanese steps into the cave. We still thought the typhoon was going to hit Guam and miss Rota.

In the Cave

Families looked for areas on the cave floor to put down their pandanus sleeping mats. A space at the far back was designated as a “bathroom.” Women brought out the cooked rice and meat fried with onions and peppers they had prepared for dinner. We all thought we would be sleeping in our homes later that night. No one was scared; it was almost like a village party. Throughout my stay on Rota, I would write letters and record tapes for my family back home. One of the tapes I sent home described the experience:

Families looked for areas on the cave floor to put down their pandanus sleeping mats. A space at the far back was designated as a “bathroom.” Women brought out the cooked rice and meat fried with onions and peppers they had prepared for dinner. We all thought we would be sleeping in our homes later that night. No one was scared; it was almost like a village party. Throughout my stay on Rota, I would write letters and record tapes for my family back home. One of the tapes I sent home described the experience:

|

About 3:30 in the morning we heard on the radio--not the Guam station which gave very little news about the typhoon and Rota--but the Anderson Air Force Base station, that the typhoon was going directly over Rota with winds of 120 and gusts to 160. We were the only radio (a new short wave with batteries purchased for our trip) in the cave to get this station and the signal was weak. The station also reported that the eye would go over Rota.

In the morning the winds got very intense and we could see leaves flying all over the place. Around 11:30 the eye went over, it got very calm. Some people went outside and some people thought it was over; we tried to explain that it was not. After the eye, the winds got much worse and changed direction. Even in the cave we had to sit huddled with the children inside and just sit all day while the winds beat at us with the rain. We were all tired. We were worried. During the eye the men saw that the roof was off the hospital. The post office was demolished. Roofs were off concrete houses. The convent was gone and many people had sheltered in the convent. We learned later they all went to the church. The church was shaking a bit too, even though it is very strong. So it was like that all day and we slept the next night. By this time many people had run out of food. We had extra food so we were able to share (having prepared for three days). We just slept on the ground of the cave on mats. We really slept. (#K040 tape) |

The first night in the cave we tuned into KUAM Guam radio. We listened to the broadcast that the prayers of the good people on Guam had been answered and the typhoon had missed them. However, the storm would go directly over Rota, and this would be the last typhoon report we heard. I remember saying, (but may not have) “What about us, here in the cave. Don’t leave us alone without information.” Later, Guam Press reported “Guam was spared the tremendous forces of the winds in a situation that could be compared to a miracle…It’s possible that some prayers helped save Guam from the forces of Gilda…looking at the path Gilda took, we just won’t discount the possibility that somebody down here reached somebody up there.” (Guam Daily News 10/15/1967) While in the cave, I wrote a letter:

|

Nov. 13, 1967

We have been in the typhoon cave since yesterday afternoon. It is now 9am and the noise of the wind is so loud we cannot hear and our ears hurt. Rain is blowing into the cave and it looks like smoke. Before we left our house we packed everything in one corner and covered it but now we know that our house is no longer standing. The eye was set to go over Guam but it changed and is coming over Rota. We expect winds to be 120 knots with gusts to 150 and seas to be 30 feet (that will cover the town, which is low). The cave we are in was used by the Japanese as a hospital. It is near our house, high, with two openings. It was hard to realize when we got ready to come here that everything might be destroyed. We did not bring as much as we could have. It is hard to believe this wind. It is now 5pm and it is over. No need to worry about our house going because it is gone. The eye passed at eleven our time – right over Rota. You would not believe the winds around it… We are still in the cave, the wind is bad and the rain is starting. Rain should last 2 or 3 days. From the cave we can see most of the houses destroyed and many lots are just vacant. It looks like winter the way there are no trees…. The people near us in the cave who we are sort-of living with—one family has thirteen children with one on the way this week or next. The other has twelve. And they have no house now. It is now when we are completely out of communication – town radio destroyed – no planes can come in and we need so much that I realize what CARE, Red Cross and such can do. (Letter #L016) |

Leaving the Cave

Carefully making our way down the steps, the island looked like the winter I knew in Massachusetts. This lush tropical island you could not explore outside the village without a machete to cut a path, had no green, no leaves, no flowers, no life. Coconuts that once needed strong climbers to pick them now waited to be gathered like berries, their abundance deceiving because in a few days there would be none and there would be no trees to climb for more. The tin houses were gone, folded into pieces.

Carefully making our way down the steps, the island looked like the winter I knew in Massachusetts. This lush tropical island you could not explore outside the village without a machete to cut a path, had no green, no leaves, no flowers, no life. Coconuts that once needed strong climbers to pick them now waited to be gathered like berries, their abundance deceiving because in a few days there would be none and there would be no trees to climb for more. The tin houses were gone, folded into pieces.

To my surprise, nobody cried or complained. They gathered together and rejoiced that nobody was dead and then began organizing to plan for shelter and food. Everybody seemed to know who would be best for each job and to accept their roles easily. Old ladies taught the girls how to dry meat. It was obvious that there would not be electricity again for a long time and the two small stores on the island had freezers with meat that would spoil. In addition some injured animals needed to be slaughtered. Other women cooked for the men who were starting to clean up and trying to make shelter although most would continue staying in the caves. We wondered if anybody knew about us, but it was more from curiosity than need. I wrote to my family about the day:

|

Nov. 14, 1967

It is the next day. Greg spent the day doing a survey of the village. 80% total destruction; 100% partial destruction. I tried to salvage things from our house. Just about everything is OK. The Navy flew a helicopter in with a doctor and are going to send another with needed supplies. We are going to sleep at the school tonight or with another family whose house is just missing part to the ceiling. Milk was given out today from the school milk program. The High Commissioner is coming in today, I think. We have been trying to get word to you in case you know of the storm and are worried that there is no communication. We hope to ask the High Commissioner to mail this. We are sort of numb and very tired. I think mail I sent you before the typhoon was destroyed in the now destroyed post office. (Letter #L016) |

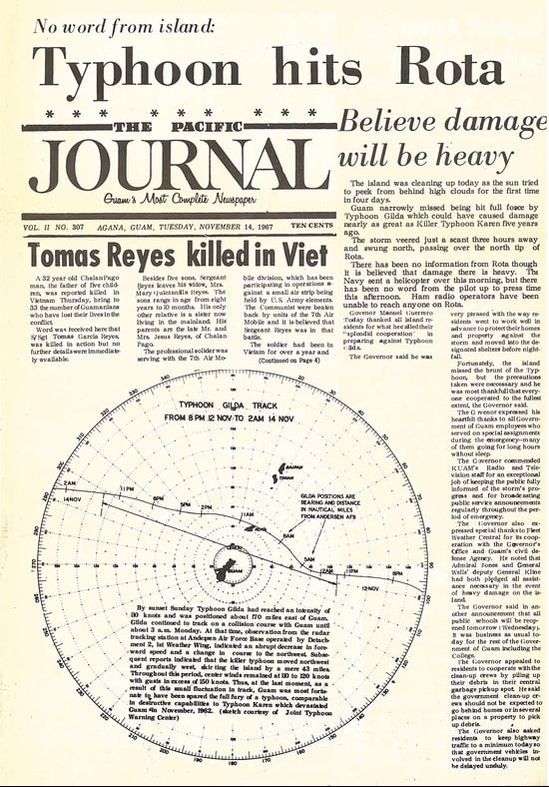

Newspaper clipping seen by my parents before I could reach them

Newspaper clipping seen by my parents before I could reach them

First Responders

Later in the afternoon a helicopter from the Navy base on Guam appeared on the horizon. It contained a doctor, a Red Cross official and a government official. We had seen planes flying around but they had not been able to land. They stayed about 15 minutes; quickly surveying the damage so plans could be drafted for how aid would be handled. The mayor did not speak English so the government representative did the talking with the officials.

In the cave, and later, I had wondered if our family in Massachusetts knew what was happening. In fact, they did. A friend of my mother’s had seen a press release (pictured right) about a small island in the Pacific and had phoned to ask if that was where I was. My father was a retired Naval officer and was able to use contacts in the Navy on Guam to check on me. So on one of the first helicopters to land, when we were all standing watching—so happy that someone was coming to help--one of the people onboard asked for me. Then we knew that our family knew what was happening and would know that we were OK.

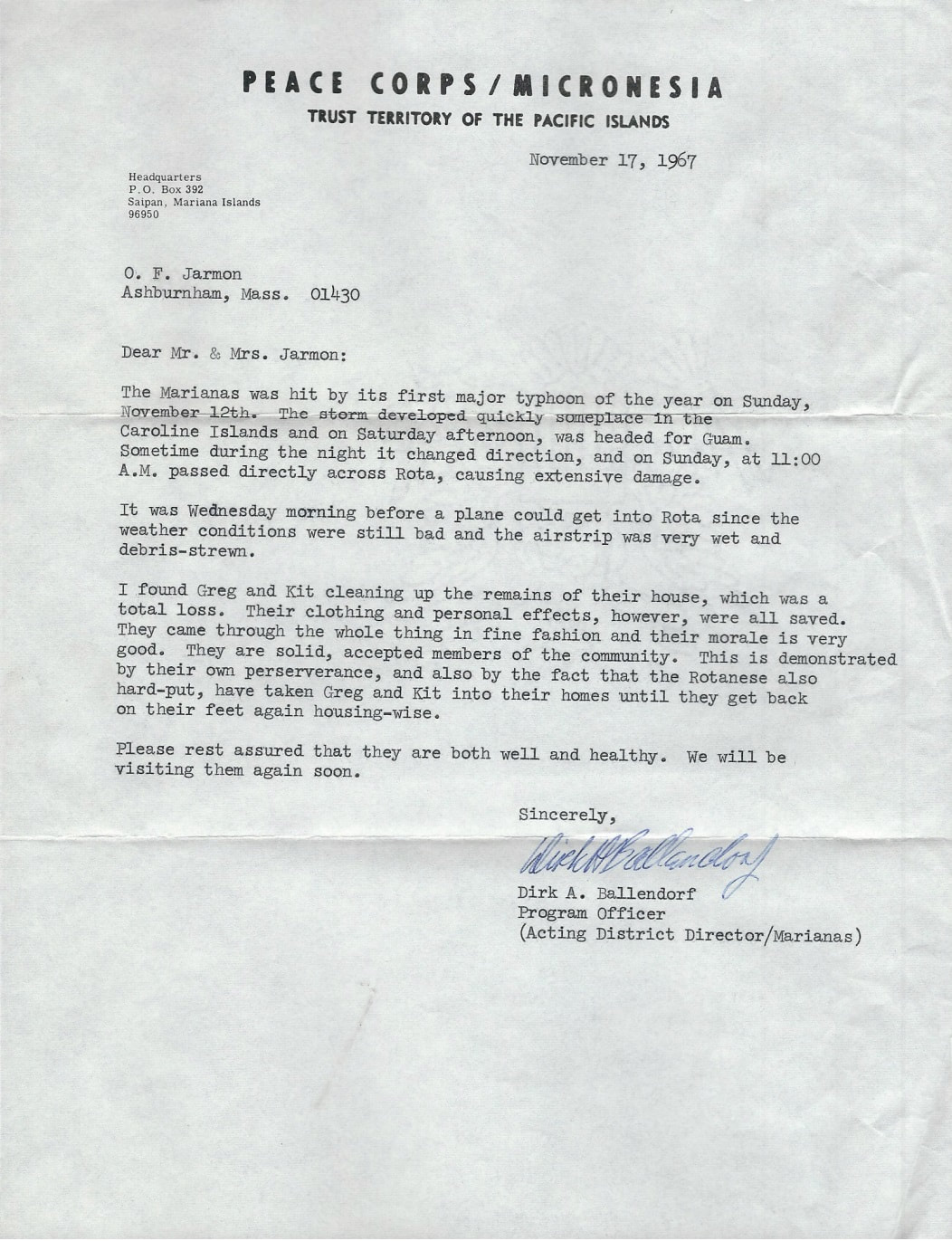

We had meat from freezers and heart of palms from the trees right after the typhoon but, with no electricity, they would not keep. We soon were almost out of food and the survey of housing determined that 80% of houses were destroyed. Peace Corps sent a representative, Dirk Ballendorf, with the first surveillance party. He wrote my parents:

Later in the afternoon a helicopter from the Navy base on Guam appeared on the horizon. It contained a doctor, a Red Cross official and a government official. We had seen planes flying around but they had not been able to land. They stayed about 15 minutes; quickly surveying the damage so plans could be drafted for how aid would be handled. The mayor did not speak English so the government representative did the talking with the officials.

In the cave, and later, I had wondered if our family in Massachusetts knew what was happening. In fact, they did. A friend of my mother’s had seen a press release (pictured right) about a small island in the Pacific and had phoned to ask if that was where I was. My father was a retired Naval officer and was able to use contacts in the Navy on Guam to check on me. So on one of the first helicopters to land, when we were all standing watching—so happy that someone was coming to help--one of the people onboard asked for me. Then we knew that our family knew what was happening and would know that we were OK.

We had meat from freezers and heart of palms from the trees right after the typhoon but, with no electricity, they would not keep. We soon were almost out of food and the survey of housing determined that 80% of houses were destroyed. Peace Corps sent a representative, Dirk Ballendorf, with the first surveillance party. He wrote my parents:

|

It was Wednesday morning before a plane could get into Rota since the weather conditions were still bad and the airstrip was very wet and debris-strewn…. I found Greg and Kit cleaning up the remains of their house…They came through the whole thing in fine fashion and the morale is very good. They are solid, accepted members of the community. (Letter #L012) |

Mr. Ballendorf also wrote the principal of the school:

|

I came specifically to see how the Peace Corps Volunteers had weathered the storm. Thanks to the helpfulness of the people of Rota, and their own stamina, they made out very well. I’m sure they will continue to be of assistance during the clean-up activity.

The Porters, as you know, were completely homeless. I have told them that the Peace Corps considers it to be their first job to get resituated in their home, no matter how long that may take. (box #42 Rota, Nov 17, 1967) |

Later during the recovery, I wrote home again:

|

Nov. 17 & 18

Today we did a survey of the town for the Red Cross to see who needed tents and canvas. Many people are sleeping outside and another storm is coming. This had to be done by noon. Then we handed out flour, cookies, sugar, milk and bread to the families. Then a load came in from the Air force with food, clothes and building materials. We unloaded this and sorted the can goods. There is so much. Two rooms full of clothes. Tomorrow we shall work on these. School will not start for quite a while.” |

First Week

|

We had another typhoon soon after Gilda aiming right at Rota, typhoon Harriet. Every house would have been gone if it had hit. But, it was only 80 knots. We spent another night in the cave. Our problem would have been flying tin, as there are so many parts of houses around. Any high winds could have hurt people. So getting to know the typhoon cave pretty well. Have spent four nights, not consecutively, in the cave.

Our first week into the recovery efforts and I was put in charge of food distribution. The sea was too rough to fish; salt water had destroyed farm crops; and there was no food in the two stores. The local stores had carried rice, oil, soy sauce, canned tuna and mackerel, sugar, coffee, and a few other items. They had been waiting for shipments before the typhoon. (KPV Nov. 21 Audio Tape) |

Food supplies brought in by the Guam/Saipan/Guam DC4 Wednesday, November 15th included:

|

Fifty-pound bags of rice, nine cases of milk, three cases of hash, one case of spam, five cases of corned beef and five bags of flour. Rota residents unloading the supplies estimated it would last one day. The Air Force officials brought eight cases of milk, 10 to 15 large bags of clothing, 60 pounds of sugar and about 200 pounds of rice. (The Pacific Journal 11/16/67 p 1)

|

The Pacific Journal November 13, headline read “STARVATION A DAY AWAY FOR DEVASTATED ROTA”. It and other papers and groups collected food for Rota and, thankfully, on November 18th a Navy tug arrived with 38 tons of supplies.

Highlights was the official news publication from the Office of the High Commissioner. The November 27, 1967 issue had a featured article on pages 1, 7 & 8. This explained requesting federal relief funds under the Federal Disaster Act and identified officials involved in assisting Rota. Pictures show the damage to the dock and official buildings. Our house is one of the destroyed homes shown and identified.

The Guam press sent reporters. My memory is of meeting a reporter on the road who complained that there was no transportation, no places to get food or people who wanted to be interviewed. We were all busy and in need of transportation and food ourselves. We had been told that only people providing aide would be allowed on the island immediately after the typhoon. The articles linked here seem to support what I remember, “There We Were, Stranded on Rota.” (The Pacific Journal Nov 26, 1967). Other articles describe what happened as well as assistance that was given.

When aid started coming in to the islands it became obvious why I had been given the food distribution role - unknown to myself; I was an expert on American packaged food. I divided food into groups of vegetables, meats, starches, sweets and unusable. How could anyone make Jell-O even if they knew what it was? I was told how many people there were in each family. We needed an allotment of food along with everyone else. Later when the USDA food arrived with no instructions, I attempted to teach such things as what beans are and how to cook them and that powdered milk needed to be mixed with water in order to be digestible; most people fed the cheese to the pigs.

A woman who was considered to know all the families best was tasked with distributing all the donated clothes. After each family got its pile - immediate family size averaged ten to fifteen - clothes changed hands all through the village. While the women tended to these needs, the men grouped to fix houses not totally destroyed and shelter was located for everyone.

My House

My house was one of the ones destroyed. All the doors and windows we boarded remained boarded, but the rest of the house collapsed. We lived with a family for a few months sleeping on the mat with the other family members and helping with the household chores as I could, although it was expected that I would assist with food distribution.

Highlights was the official news publication from the Office of the High Commissioner. The November 27, 1967 issue had a featured article on pages 1, 7 & 8. This explained requesting federal relief funds under the Federal Disaster Act and identified officials involved in assisting Rota. Pictures show the damage to the dock and official buildings. Our house is one of the destroyed homes shown and identified.

The Guam press sent reporters. My memory is of meeting a reporter on the road who complained that there was no transportation, no places to get food or people who wanted to be interviewed. We were all busy and in need of transportation and food ourselves. We had been told that only people providing aide would be allowed on the island immediately after the typhoon. The articles linked here seem to support what I remember, “There We Were, Stranded on Rota.” (The Pacific Journal Nov 26, 1967). Other articles describe what happened as well as assistance that was given.

When aid started coming in to the islands it became obvious why I had been given the food distribution role - unknown to myself; I was an expert on American packaged food. I divided food into groups of vegetables, meats, starches, sweets and unusable. How could anyone make Jell-O even if they knew what it was? I was told how many people there were in each family. We needed an allotment of food along with everyone else. Later when the USDA food arrived with no instructions, I attempted to teach such things as what beans are and how to cook them and that powdered milk needed to be mixed with water in order to be digestible; most people fed the cheese to the pigs.

A woman who was considered to know all the families best was tasked with distributing all the donated clothes. After each family got its pile - immediate family size averaged ten to fifteen - clothes changed hands all through the village. While the women tended to these needs, the men grouped to fix houses not totally destroyed and shelter was located for everyone.

My House

My house was one of the ones destroyed. All the doors and windows we boarded remained boarded, but the rest of the house collapsed. We lived with a family for a few months sleeping on the mat with the other family members and helping with the household chores as I could, although it was expected that I would assist with food distribution.

Life Getting Back to Normal

Months later, when the men had put the roof back on the school and those living in the school had new shelter, I started teaching again. This time I knew the families quite well. I now knew who was sister to the store owner or daughter to the mayor. The commonly used nick names indicating family traits made sense. When fish arrived at my doorstep in the middle of the night, I knew they were from the family whose child I had worked with after school. One day, I walked in the procession from the church all around the village following the statue of the village saint. All the villagers chanted, bowing respectfully to the old people resting in doorways unable to join the procession. We ended at the park under the typhoon cave, the entire community sharing a feast that had been in preparation for weeks. My role had been chopping vegetables, exactly what I was good at, when it came to cooking island food. I felt, for the first time, that I was really part of the community - a resident, not a visitor.

More Typhoon Warnings

Gradually, I got use to typhoon warnings as that became part of normal life. My important belongings, which had once filled hurriedly packed boxes, now filled a small box – passport, shot card, letters not answered, favorite pictures, pills, spam, rice, ship biscuits, peanut butter and water.

Reflections 50 Years Later

I would experience other typhoons on Rota and later during 8 years on Saipan, but none as extreme. The people in the Marianas knew what to do, how to prepare and how to help others to prepare. The Disaster Relief Act of 1974 (PL 93-288) resulted in the 1978 CNMI Disaster Emergency Plan with at least six annex publications as well as a pamphlet, “Be Prepared for Disaster.” (Box #1)

In 1981 the CNMI Civil Defense Coordinator Published “Disaster Response and Operations” detailing responses to all sorts of disasters. “Disaster Response Procedures 1983” detailed by department exact duties of individuals, as well as “Do’s and Don’ts for families before, during and after typhoon.” In 1983, as president of Northern Marianas College, I knew when to prepare the college buildings to be shelters, and that I would go to the Command Post at Condition II. The college assisted with preparation training for all sorts of disasters, including if a plane would crash on the island. Whatever the event, always, someone would come to help me prepare and to check afterwards that I was OK—even for a banana typhoon, a storm that took down only banana trees. Once during a small typhoon I couldn’t get out of my house because of trees that fell in front of the doors. Even though I was trapped, I never felt afraid and knew that the island’s population was as prepared as it could be.

Months later, when the men had put the roof back on the school and those living in the school had new shelter, I started teaching again. This time I knew the families quite well. I now knew who was sister to the store owner or daughter to the mayor. The commonly used nick names indicating family traits made sense. When fish arrived at my doorstep in the middle of the night, I knew they were from the family whose child I had worked with after school. One day, I walked in the procession from the church all around the village following the statue of the village saint. All the villagers chanted, bowing respectfully to the old people resting in doorways unable to join the procession. We ended at the park under the typhoon cave, the entire community sharing a feast that had been in preparation for weeks. My role had been chopping vegetables, exactly what I was good at, when it came to cooking island food. I felt, for the first time, that I was really part of the community - a resident, not a visitor.

More Typhoon Warnings

Gradually, I got use to typhoon warnings as that became part of normal life. My important belongings, which had once filled hurriedly packed boxes, now filled a small box – passport, shot card, letters not answered, favorite pictures, pills, spam, rice, ship biscuits, peanut butter and water.

Reflections 50 Years Later

I would experience other typhoons on Rota and later during 8 years on Saipan, but none as extreme. The people in the Marianas knew what to do, how to prepare and how to help others to prepare. The Disaster Relief Act of 1974 (PL 93-288) resulted in the 1978 CNMI Disaster Emergency Plan with at least six annex publications as well as a pamphlet, “Be Prepared for Disaster.” (Box #1)

In 1981 the CNMI Civil Defense Coordinator Published “Disaster Response and Operations” detailing responses to all sorts of disasters. “Disaster Response Procedures 1983” detailed by department exact duties of individuals, as well as “Do’s and Don’ts for families before, during and after typhoon.” In 1983, as president of Northern Marianas College, I knew when to prepare the college buildings to be shelters, and that I would go to the Command Post at Condition II. The college assisted with preparation training for all sorts of disasters, including if a plane would crash on the island. Whatever the event, always, someone would come to help me prepare and to check afterwards that I was OK—even for a banana typhoon, a storm that took down only banana trees. Once during a small typhoon I couldn’t get out of my house because of trees that fell in front of the doors. Even though I was trapped, I never felt afraid and knew that the island’s population was as prepared as it could be.

Story Gallery

Post Typhoon Photos Album

(Click the photo below to view the album)

Related/Additional Documents

- Disaster Response Procedures (1983)

- Guam Daily News, vol XXII , no. 311 Nov 15, 1967 - Miracle Saved Guam from Gilda: Rota Slammed by Typhoon that Missed Here (pg. 1)*

- Guam Daily News, vol XXII , no. 311 Nov 15, 1967 - Gilda...an Almost Tragedy (pg. 4)

- Guam Daily News, vol XXII, no. 312, Nov. 16, 1967 - Gilda Leaves Rota in Shambles (pg. 1)

- Guam Daily News, Nov 17, 1967 - Supplies Rushed to Rota (pg. 24)*

- Highlights, Nov 27, 1967 (pg. 1, 7, 8)*

- Highlights, Dec 25, 1967 - Disaster Aid Turned Down (pg. 1)*

- Marianas Bulletin, Vol I, no. 47, Dec 22, 1967 - Washington Turns Down Typhoon Aid Request (pg. 1, 5)*

- Micronesian Reporter, Sept/Dec 1967 - Typhoon (pg. 25-27) (5 pict of Rota—one of Kit in her house)*

- The Pacific Journal, Vol. II, no. 307, Nov 14, 1967 - No Word from Island: Typhoon Hits Rota (pg. 1)

- The Pacific Journal, Vol II, no. 309, Nov 16, 1967 - Starvation a Day Away from Devastated Rota (pg. 1)

- The Pacific Journal, Nov 17, 1967 (pg. 13)

- The Pacific Journal, Nov. 24, 1967 - Mercy Mission...from Guam to Rota (pg. 13)

- The Pacific Journal, Nov 26, 1967 - There We Were Stranded on Rota (pg. 12, 13)

- The Pacific Journal, Nov. 13, 1967 - Typhoon Hits Rota (pg. 1)

- Peace Corps Volunteer, Jan 1968 (pg. 21)

- [Clipping about Typhoon Gilda]

Source Info

- KPV Collection - Box #1, Weather/Disasters

- KPV Collection - Box #52, Letters: #L011 & #L013

- KPV Collection - Box #55

- KPV Collection - Box #42, Rota

- KPV Collection - Audio: #K037a, #K038, #K040

© Kit Porter Van Meter Marianas Collection 2017