MicrOlympics 1969 Games

Written & Arranged by Tom Zink

|| Intro | Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Comments ||

Early Stages

Beginnings

The idea for a territory-wide athletic competition for Micronesia began to take shape in late 1967. Two Saipan PCVs, Kurt Barnes and Al Snyder, shared a vision for a region-wide sports competition. Along with Felix F. Rabauliman, a Saipanese Carolinian leader, they brought together a group to explore the possibility of an Olympic-style event. Funded by the Peace Corps, the group included an islander and a Peace Corps representative from each district: Fred Dellimuth and Tony Towai from Palau; Troy Barker and Dr. Jack Helkena from the Marshalls; Loren Peterson and Kozo Yamada from Ponape; Frank Aikman and Nick Bossy from Truk; Al Snyder, Kurt Barnes, and Felix Rabauliman from the Marianas; and Gilmoon and a PC rep from Yap we’ve not been able to identify. As the capital of Micronesia, Saipan’s population (about 10,000 at the time) included Americans and Micronesians from the other districts who lived and worked there, Chamorros and Carolinians whose home island was Saipan, and several dozen PCVs, many with strong backgrounds in sports. For this first attempt to bring athletes together from such a large geographical area, Saipan was the logical choice to serve as host island.

Challenges

But many challenges confronted this planning group. Some existing sports facilities on Saipan had been damaged or destroyed by the recent Typhoon Jean in April 1968. A basketball court at Mt. Carmel School had lost its roof in the typhoon. A concrete tennis court, left over from World War II, near the District Legislature building in Susupe, was neglected and so overgrown with a small, fast-growing tree that spread like weeds, called tangan-tangan, you could barely see it from Beach Road. Saipan lacked a swimming pool, a 400-meter track, volleyball courts, and regulation-sized table tennis tables. Not to mention the overriding question: Where would the money come from to transport athletes from the other districts, to build the required facilities, to purchase uniforms and equipment, to feed and house the athletes? And other more cultural questions, like, would the Yapese men compete in their thus (loincloths), or would fears of “island magic” become an issue?

The idea for a territory-wide athletic competition for Micronesia began to take shape in late 1967. Two Saipan PCVs, Kurt Barnes and Al Snyder, shared a vision for a region-wide sports competition. Along with Felix F. Rabauliman, a Saipanese Carolinian leader, they brought together a group to explore the possibility of an Olympic-style event. Funded by the Peace Corps, the group included an islander and a Peace Corps representative from each district: Fred Dellimuth and Tony Towai from Palau; Troy Barker and Dr. Jack Helkena from the Marshalls; Loren Peterson and Kozo Yamada from Ponape; Frank Aikman and Nick Bossy from Truk; Al Snyder, Kurt Barnes, and Felix Rabauliman from the Marianas; and Gilmoon and a PC rep from Yap we’ve not been able to identify. As the capital of Micronesia, Saipan’s population (about 10,000 at the time) included Americans and Micronesians from the other districts who lived and worked there, Chamorros and Carolinians whose home island was Saipan, and several dozen PCVs, many with strong backgrounds in sports. For this first attempt to bring athletes together from such a large geographical area, Saipan was the logical choice to serve as host island.

Challenges

But many challenges confronted this planning group. Some existing sports facilities on Saipan had been damaged or destroyed by the recent Typhoon Jean in April 1968. A basketball court at Mt. Carmel School had lost its roof in the typhoon. A concrete tennis court, left over from World War II, near the District Legislature building in Susupe, was neglected and so overgrown with a small, fast-growing tree that spread like weeds, called tangan-tangan, you could barely see it from Beach Road. Saipan lacked a swimming pool, a 400-meter track, volleyball courts, and regulation-sized table tennis tables. Not to mention the overriding question: Where would the money come from to transport athletes from the other districts, to build the required facilities, to purchase uniforms and equipment, to feed and house the athletes? And other more cultural questions, like, would the Yapese men compete in their thus (loincloths), or would fears of “island magic” become an issue?

“If the thu fits . . .”

These questions caused some doubt and hesitation at first. The decision to move forward with the MicrOlympics would require a giant leap of faith by this ad hoc group of sports enthusiasts. The lack of facilities did not deter them. The unanswered questions paled in comparison to the unprecedented opportunity a Micronesian Olympic Games promised: to bring together for nine days the many cultures, languages, and peoples of Micronesia to celebrate excellence in athletic competition. With the decision hanging in the balance, Kurt Barnes quipped, “Well, if the thu fits, wear it.”

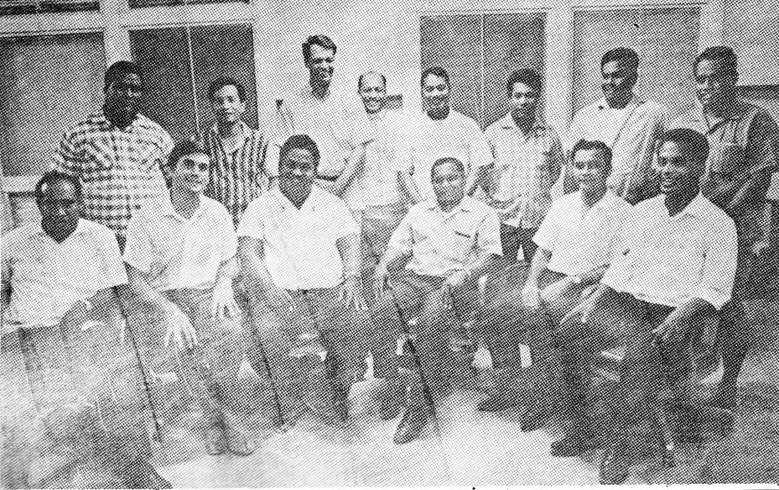

The entire room burst out in uproarious laughter, a sure sign that the Games were on. They all came together around this common goal. The official MicrOlympics Committee (pictured below) was then formed with representatives from all six districts. Felix Rabauliman became the chairman (3rd from left, front row), Al Snyder the secretary general (2nd from left, front row), Kurt Barnes (back row, 3rd from left), who by now was employed by the Marianas Education Department, represented the Marianas, and a Saipan businessman, David M. Sablan (back row, 4th from left), was recruited for the vital role of Director of Funds. Sablan was able to secure $175,000 of funding from the Congress of Micronesia to cover expenses for travel, food, logistics, and housing necessary to host the Games.

These questions caused some doubt and hesitation at first. The decision to move forward with the MicrOlympics would require a giant leap of faith by this ad hoc group of sports enthusiasts. The lack of facilities did not deter them. The unanswered questions paled in comparison to the unprecedented opportunity a Micronesian Olympic Games promised: to bring together for nine days the many cultures, languages, and peoples of Micronesia to celebrate excellence in athletic competition. With the decision hanging in the balance, Kurt Barnes quipped, “Well, if the thu fits, wear it.”

The entire room burst out in uproarious laughter, a sure sign that the Games were on. They all came together around this common goal. The official MicrOlympics Committee (pictured below) was then formed with representatives from all six districts. Felix Rabauliman became the chairman (3rd from left, front row), Al Snyder the secretary general (2nd from left, front row), Kurt Barnes (back row, 3rd from left), who by now was employed by the Marianas Education Department, represented the Marianas, and a Saipan businessman, David M. Sablan (back row, 4th from left), was recruited for the vital role of Director of Funds. Sablan was able to secure $175,000 of funding from the Congress of Micronesia to cover expenses for travel, food, logistics, and housing necessary to host the Games.

A full list of Committee members can be found here.

Choosing the Events

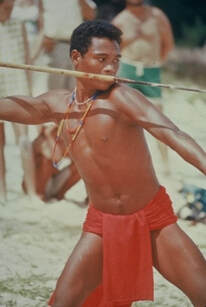

Of the nine events chosen for this first MicrOlympics, two would be uniquely Micronesian: outrigger canoe races, both paddling and sailing, and the Micronesian All-Around, an island-style pentathlon of five contests—coconut-tree climbing, coconut husking, spear-throwing, underwater swimming, and underwater diving. The other seven events were basketball, baseball, swimming, table tennis, tennis, track and field, and volleyball. Kurt Barnes recalls that some committee members wanted to include sumo wrestling, but that idea was nixed.

A Threatening Letter

Sometime in the fall of 1968 when plans were starting to pick up steam, Al Snyder received a rather nasty letter from a lawyer at the International Olympic Committee (IOC). The letter claimed that Micronesia’s use of the term “Olympics” was copyright infringement, and the term should be dropped. The “Olympic” term was gaining currency in Micronesia by that time, and the organizing committee decided to retain it and continue full speed ahead. After the 1969 MicrOlympics, the next time a Micronesia-wide sporting event took place (1990), the “Olympics” was dropped, and it was called the “Micronesian Games.”

Of the nine events chosen for this first MicrOlympics, two would be uniquely Micronesian: outrigger canoe races, both paddling and sailing, and the Micronesian All-Around, an island-style pentathlon of five contests—coconut-tree climbing, coconut husking, spear-throwing, underwater swimming, and underwater diving. The other seven events were basketball, baseball, swimming, table tennis, tennis, track and field, and volleyball. Kurt Barnes recalls that some committee members wanted to include sumo wrestling, but that idea was nixed.

A Threatening Letter

Sometime in the fall of 1968 when plans were starting to pick up steam, Al Snyder received a rather nasty letter from a lawyer at the International Olympic Committee (IOC). The letter claimed that Micronesia’s use of the term “Olympics” was copyright infringement, and the term should be dropped. The “Olympic” term was gaining currency in Micronesia by that time, and the organizing committee decided to retain it and continue full speed ahead. After the 1969 MicrOlympics, the next time a Micronesia-wide sporting event took place (1990), the “Olympics” was dropped, and it was called the “Micronesian Games.”