MicrOlympics 1969 Games

Written & Arranged by Tom Zink

|| Intro | Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Comments ||

Setting the Stage

“If you build it, they will come” was a recurring mantra from the 1989 film “Field of Dreams.” Building the sports facilities for the MicrOlympics on Saipan became a matter of “Build it . . . before they come.” Some of the event locations—baseball, canoe racing, and the Micronesian All-Around—required only minor preparations prior to the early July arrival of teams from the other islands. Significant conceptual, design, and construction work was required to complete the facilities for the other six events. Some of those projects were completed in a timely fashion; others came right down to the wire, not unlike stories we read about venue construction for international Olympic events.

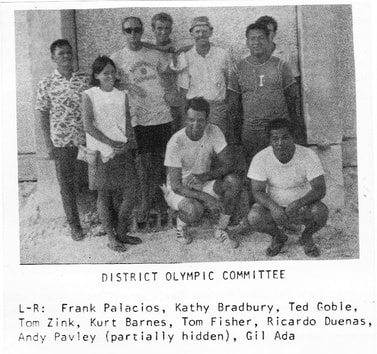

Marianas Athletic Association

The group that took responsibility on the host island for coordinating facilities construction, selecting, coaching, and equipping the district’s teams, and a myriad of other tasks was the Marianas Athletic Association (MAA). Committee members included Gil Ada, director, and Rick Duenas, assistant director, of the Marianas Community Development office, Vic Cepeda, Frank Palacios, and Kurt Barnes. PCVs on the committee were Kathy Bradbury, Dave Crutcher, Tom Fisher, Ted Goble, Andy Pavley, and Tom Zink. Coaching assignments for Marianas teams were as follows: Baseball—Gil Ada, Basketball—Tom Fisher, Swimming—Ted Goble and Kathy Bradbury, Track and Field—Andy Pavley, Volleyball—Kurt Barnes and Tom Zink. The Community Development office secured $5,000 in funding for uniforms and equipment from the District Legislature.

Most of the athletes chosen to represent the Marianas were from Saipan, but efforts were made to include athletes from Tinian and Rota. A few months before the Games were to begin, Kurt Barnes and Andy Pavley, Marianas track coach, got word of a very fast runner on Rota. They flew to Rota and asked around trying to find him, and find him they did. In jail. The only way he could be released to run a time trial was with a police officer to accompany him. Under the policeman’s watchful eye, Kurt and Andy measured out 100 meters on Rota’s main road, hoping the young man would not take off and sprint into the jungle. But he didn’t: he outran Andy, a strong runner who’d competed in college, and earned himself a spot on the Marianas track and field team.

The group that took responsibility on the host island for coordinating facilities construction, selecting, coaching, and equipping the district’s teams, and a myriad of other tasks was the Marianas Athletic Association (MAA). Committee members included Gil Ada, director, and Rick Duenas, assistant director, of the Marianas Community Development office, Vic Cepeda, Frank Palacios, and Kurt Barnes. PCVs on the committee were Kathy Bradbury, Dave Crutcher, Tom Fisher, Ted Goble, Andy Pavley, and Tom Zink. Coaching assignments for Marianas teams were as follows: Baseball—Gil Ada, Basketball—Tom Fisher, Swimming—Ted Goble and Kathy Bradbury, Track and Field—Andy Pavley, Volleyball—Kurt Barnes and Tom Zink. The Community Development office secured $5,000 in funding for uniforms and equipment from the District Legislature.

Most of the athletes chosen to represent the Marianas were from Saipan, but efforts were made to include athletes from Tinian and Rota. A few months before the Games were to begin, Kurt Barnes and Andy Pavley, Marianas track coach, got word of a very fast runner on Rota. They flew to Rota and asked around trying to find him, and find him they did. In jail. The only way he could be released to run a time trial was with a police officer to accompany him. Under the policeman’s watchful eye, Kurt and Andy measured out 100 meters on Rota’s main road, hoping the young man would not take off and sprint into the jungle. But he didn’t: he outran Andy, a strong runner who’d competed in college, and earned himself a spot on the Marianas track and field team.

A Floating Pool

In 1968, Saipan had no swimming pool, but plenty of water in its lagoon. One of the most creative adaptations to local conditions was the development of a swimming pool for the MicrOlympics competition. PCV Ted Goble came up with a simple concept to float some empty oil drums, build two plywood platforms on top to hold them together, and anchor them 25 yards apart alongside a dock in Garapan. In true island style, the lane markers were kept afloat by coconuts painted white. Note the lane markers in this photo of Marianas swimmer, Frank Rogopes. Plywood marked with X’s was installed in the water, so the swimmers would know where the wall was. The pool was built for about $500.

The construction of the swimming pool was a great example of the true community spirit that came together for the Games. Goble noted that Peace Corps people were in Micronesia as volunteers and that’s what they did, for this and many other projects. Many others helped as well, Micronesians and Americans who were all willing to give of their time to help ensure the Games would succeed.

The Marianas Swimming Trials were held in late April in this new island-style pool. But the organizers had to come up with a Plan B: a short time after the Trials, a tropical storm came along and blew everything out to sea. “The first pool just kinda floated away,” said Goble. They built a second pool, but added a walkway between the two platforms at either end to make it more stable. It began as an official-length pool, but with the ebb and flow of the tides, the length varied between 24 and 27 yards.

In 1968, Saipan had no swimming pool, but plenty of water in its lagoon. One of the most creative adaptations to local conditions was the development of a swimming pool for the MicrOlympics competition. PCV Ted Goble came up with a simple concept to float some empty oil drums, build two plywood platforms on top to hold them together, and anchor them 25 yards apart alongside a dock in Garapan. In true island style, the lane markers were kept afloat by coconuts painted white. Note the lane markers in this photo of Marianas swimmer, Frank Rogopes. Plywood marked with X’s was installed in the water, so the swimmers would know where the wall was. The pool was built for about $500.

The construction of the swimming pool was a great example of the true community spirit that came together for the Games. Goble noted that Peace Corps people were in Micronesia as volunteers and that’s what they did, for this and many other projects. Many others helped as well, Micronesians and Americans who were all willing to give of their time to help ensure the Games would succeed.

The Marianas Swimming Trials were held in late April in this new island-style pool. But the organizers had to come up with a Plan B: a short time after the Trials, a tropical storm came along and blew everything out to sea. “The first pool just kinda floated away,” said Goble. They built a second pool, but added a walkway between the two platforms at either end to make it more stable. It began as an official-length pool, but with the ebb and flow of the tides, the length varied between 24 and 27 yards.

Table Tennis

PCV Dave Crutcher offered to take the lead for table tennis. There were no regulation tables on Saipan at the time, nor were there funds to purchase and ship brand new tables to Saipan. They needed to construct their own. With the help of Peace Corps carpenter Gene Sloan and a couple of Saipanese plus the specs for regulation ping pong tables from a rule book Dave’s father had mailed him, they built four tables, using saw horses made of 2 x 4s for the legs. For the table tops, they secured some surplus mahogany plywood shipped from the Philippines after Typhoon Jean. The boards were then sanded well, painted green, and positioned on the saw horses completely level and at regulation height.

Table tennis is a game that needs to be played indoors, especially on a tropical Pacific island with its variable breezes and the blazing heat of the sun. The site chosen for the MicrOlympics was the Chalan Kanoa school auditorium, a Butler building with a level concrete floor that sustained minimal damage from Typhoon Jean in April 1968. Repairs made in the following months ensured its suitability for the MicrOlympics.

PCV Dave Crutcher offered to take the lead for table tennis. There were no regulation tables on Saipan at the time, nor were there funds to purchase and ship brand new tables to Saipan. They needed to construct their own. With the help of Peace Corps carpenter Gene Sloan and a couple of Saipanese plus the specs for regulation ping pong tables from a rule book Dave’s father had mailed him, they built four tables, using saw horses made of 2 x 4s for the legs. For the table tops, they secured some surplus mahogany plywood shipped from the Philippines after Typhoon Jean. The boards were then sanded well, painted green, and positioned on the saw horses completely level and at regulation height.

Table tennis is a game that needs to be played indoors, especially on a tropical Pacific island with its variable breezes and the blazing heat of the sun. The site chosen for the MicrOlympics was the Chalan Kanoa school auditorium, a Butler building with a level concrete floor that sustained minimal damage from Typhoon Jean in April 1968. Repairs made in the following months ensured its suitability for the MicrOlympics.

Two Courts in One

The neglected, overgrown World War II tennis court was to become the site for the tennis tournament, neglected and overgrown being the key words. Saipan Public Works brought in heavy equipment to clear away the tangan-tangan, fences were installed along the perimeter on both ends of the court, and the white boundary lines for tennis were re-painted. Complications ensued when this court was chosen for the basketball competition as well.

The neglected, overgrown World War II tennis court was to become the site for the tennis tournament, neglected and overgrown being the key words. Saipan Public Works brought in heavy equipment to clear away the tangan-tangan, fences were installed along the perimeter on both ends of the court, and the white boundary lines for tennis were re-painted. Complications ensued when this court was chosen for the basketball competition as well.

With less than a month to go before the opening ceremonies, Public Works installed the support posts and the basketball backboards. Basketball regulations call for the backboards to extend out over the court surface by four feet. The tennis organizers noticed this overhang and complained that the backboards would interfere with tennis play. Public Works was called in again, this time to adapt the basketball support posts so the backboards could be swiveled out of the way during tennis matches. Baskets were finally attached to the backboards three days before the Games began. This photo shows the position of the backboards for a basketball game.

The baskets were ready, but the court had no lines. On a typically hot, humid June day on Saipan, PCV Tom Fisher found himself at Joeten Shopping Center, roaming the aisles for blue paint and masking tape to mark the basketball court lines. With help from a couple other volunteers, working on their hands and knees, they marked and painted the lines with just a couple days left to go.

The baskets were ready, but the court had no lines. On a typically hot, humid June day on Saipan, PCV Tom Fisher found himself at Joeten Shopping Center, roaming the aisles for blue paint and masking tape to mark the basketball court lines. With help from a couple other volunteers, working on their hands and knees, they marked and painted the lines with just a couple days left to go.

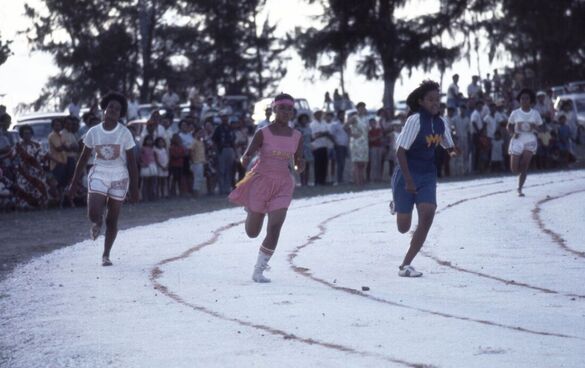

Track and Field

A large, flat undeveloped tract of land just south of Oleai village on Beach Road was chosen as the track and field site. Peace Corps engineers designed the lay-out for a 400-meter track with six lanes, each lane four feet wide. Stakes driven into the ground guided a Public Works grader and a bulldozer when they came in the middle of May to clear the brush and prepare the ground for the track. For several weeks, dump trucks delivered loads of crushed coral to the site. The final load of coral was dumped on June 8, 25 days before the start of the Games.

It took another week for all the piles of coral to be graded out and rolled smooth. The next phase of preparing the track was watering the running surfaces. Several PCVs took turns driving a very slow-moving, water-sprinkling truck around and around the track. There was less than a week left before the opening ceremonies.

With three days to go until lift-off, a crew of PCVs, including Tom Fisher, Andy Pavley, Tom Zink, and Kurt Barnes began the task of marking the six lanes on the track. They filled small cans with oil from a large Mobil Corp. drum and carefully poured oil into the parallel lines that had been scratched four feet apart all around the 400-meter track. Between measuring, marking, and painting or oiling lines for the basketball court, volleyball courts, and the track, one PCV recalled that they spent a lot of time on their knees.

A large, flat undeveloped tract of land just south of Oleai village on Beach Road was chosen as the track and field site. Peace Corps engineers designed the lay-out for a 400-meter track with six lanes, each lane four feet wide. Stakes driven into the ground guided a Public Works grader and a bulldozer when they came in the middle of May to clear the brush and prepare the ground for the track. For several weeks, dump trucks delivered loads of crushed coral to the site. The final load of coral was dumped on June 8, 25 days before the start of the Games.

It took another week for all the piles of coral to be graded out and rolled smooth. The next phase of preparing the track was watering the running surfaces. Several PCVs took turns driving a very slow-moving, water-sprinkling truck around and around the track. There was less than a week left before the opening ceremonies.

With three days to go until lift-off, a crew of PCVs, including Tom Fisher, Andy Pavley, Tom Zink, and Kurt Barnes began the task of marking the six lanes on the track. They filled small cans with oil from a large Mobil Corp. drum and carefully poured oil into the parallel lines that had been scratched four feet apart all around the 400-meter track. Between measuring, marking, and painting or oiling lines for the basketball court, volleyball courts, and the track, one PCV recalled that they spent a lot of time on their knees.

The Olympic Torch Flames Out

The Olympic Committee made plans to emulate some of the key rituals that marked the opening of international Olympic events, like the torch relay and the Olympic cauldron. Late in the day on July 3, a large bonfire was lit on Mount Topachau, the island’s highest point, renamed for that one night as Saipan’s “Mount Olympus.” The bonfire was visible from the Olympic track on Beach Road in Susupe more than 1,500 feet below.

The Olympic torch would be lit from that fire, relayed down the mountain, then carried into the opening ceremonies at the track and field stadium by the Marianas athlete chosen for the honor. He would then light the large caldron that would burn for the nine days of competition. That was the plan. Here’s how it played out.

Mounted on a six-foot high concrete trapezoid-shaped stand, the metal caldron was connected to a kerosene tank inside the stand. The kerosene was to feed the flame and keep it burning throughout the Games. On the day before the opening ceremonies, officials conducted a "dry run" test of the caldron. When the inside of the caldron was ignited, the flame flared up, as expected. One can imagine that what happened next was greeted with surprise, a few expletives, a few jokes, and “What now?” The metal bowl gave way to the heat and slowly melted, splitting into four pieces. It was time for another Plan B.

Kurt Barnes remembers that Ben Fitial hurried to his grandmother’s house in nearby Oleai village and brought back a gigantic Carolinian cook pot. They placed a pile of rags and toilet paper into the pot, soaked them in kerosene, and tried again. This time it worked. The pot did not melt. The veteran, blackened pot that over the years had cooked large quantities of rice over an outdoor wood cooking stove had become the Olympic cauldron.

Arrivals

David Sablan, the Director of Funds for the MicrOlympic organizing committee, secured the assistance of the U.S. military on Guam to transport the Olympic teams to Saipan. Some teams flew on C-130 Hercules transport planes. The athletes from Truk, Palau, and Ponape were the first to arrive on July 1. They were warmly welcomed at the airport, where they were greeted with flowered leis and mwarmwars and boarded buses for the short ride to the Olympic Village at Hopwood High School. The teams arrived with their coaches and officials, many of whom were Peace Corps Volunteers. Kurt Barnes said that “we couldn’t have done this without all the PCVs in all the districts preparing their teams and helping as officials at the Games.” The teams from the Marshalls and Yap arrived a day later.

The Olympic Committee made plans to emulate some of the key rituals that marked the opening of international Olympic events, like the torch relay and the Olympic cauldron. Late in the day on July 3, a large bonfire was lit on Mount Topachau, the island’s highest point, renamed for that one night as Saipan’s “Mount Olympus.” The bonfire was visible from the Olympic track on Beach Road in Susupe more than 1,500 feet below.

The Olympic torch would be lit from that fire, relayed down the mountain, then carried into the opening ceremonies at the track and field stadium by the Marianas athlete chosen for the honor. He would then light the large caldron that would burn for the nine days of competition. That was the plan. Here’s how it played out.

Mounted on a six-foot high concrete trapezoid-shaped stand, the metal caldron was connected to a kerosene tank inside the stand. The kerosene was to feed the flame and keep it burning throughout the Games. On the day before the opening ceremonies, officials conducted a "dry run" test of the caldron. When the inside of the caldron was ignited, the flame flared up, as expected. One can imagine that what happened next was greeted with surprise, a few expletives, a few jokes, and “What now?” The metal bowl gave way to the heat and slowly melted, splitting into four pieces. It was time for another Plan B.

Kurt Barnes remembers that Ben Fitial hurried to his grandmother’s house in nearby Oleai village and brought back a gigantic Carolinian cook pot. They placed a pile of rags and toilet paper into the pot, soaked them in kerosene, and tried again. This time it worked. The pot did not melt. The veteran, blackened pot that over the years had cooked large quantities of rice over an outdoor wood cooking stove had become the Olympic cauldron.

Arrivals

David Sablan, the Director of Funds for the MicrOlympic organizing committee, secured the assistance of the U.S. military on Guam to transport the Olympic teams to Saipan. Some teams flew on C-130 Hercules transport planes. The athletes from Truk, Palau, and Ponape were the first to arrive on July 1. They were warmly welcomed at the airport, where they were greeted with flowered leis and mwarmwars and boarded buses for the short ride to the Olympic Village at Hopwood High School. The teams arrived with their coaches and officials, many of whom were Peace Corps Volunteers. Kurt Barnes said that “we couldn’t have done this without all the PCVs in all the districts preparing their teams and helping as officials at the Games.” The teams from the Marshalls and Yap arrived a day later.

The only female in that first official welcoming group was Fay Nelson, a PCV teacher on Rota, who was on Saipan for the summer. Just the week before, Fay had been asked to be the “housemother” for all the visiting female athletes, many of whom were off their home island for the first time. You can read about her “housemother” experiences in “Fay Giordano’s MicrOlympics journal.”

Many of the girls Fay was in charge of had never run in shoes before. Unbelievable blisters developed, and Fay looked after them in the first aid room at the Olympic Village. One day after Fay had bandaged a girl’s blisters, an athlete in a Ponapean t-shirt walked into the room and said his back was bothering him. Fay offered her help and gave him a brief massage for his sore back. Stay tuned for the rest of this story.

Many of the girls Fay was in charge of had never run in shoes before. Unbelievable blisters developed, and Fay looked after them in the first aid room at the Olympic Village. One day after Fay had bandaged a girl’s blisters, an athlete in a Ponapean t-shirt walked into the room and said his back was bothering him. Fay offered her help and gave him a brief massage for his sore back. Stay tuned for the rest of this story.